June 07, 2019 12:45 PM UTC

June 07, 2019 12:45 PM UTC

This is a blog of words. Sure, we talk numbers now and then, mostly as it relates to polling or margins of victory (or The Big Line); but to the extent that we have any expertise, it is definitely more with words than numbers.

So it is with fair warning that we jump into a weird math problem that keeps showing up in analysis of the Denver Mayor’s race.

We started seeing this analysis more regularly after Lisa Calderon and Penfield Tate endorsed Giellis in the runoff, forming what headline writers liked to call a “Unity Ticket.” This idea picked up steam heading into the final weekend of the runoff, as Joe St. George wrote for Fox 31 Denver last week:

At the very basic level, Hancock faces a math disadvantage going into Tuesday’s runoff.

60% of voters who participated in the May election voted for someone other than Hancock. Hancock received around 40%.

The recipients of most of that vote were Penfield Tate, Lisa Calderon and Jaime Giellis. Giellis finished second with 25%.

59,000 people voted for Tate and Calderon.

Both of those candidates have endorsed Giellis. Do the voters follow? Or does Hancock steal enough votes away?

This is all wrong, but more on that in a moment. There is a similar view in a post-election analysis of the race in today’s Denver Post:

Paul Teske, the dean of the University of Colorado Denver’s School of Public Affairs, said Hancock’s lackluster performance during the first-round election last month didn’t mean that everyone who voted against him then would do the same this week.

“It probably reflects that we don’t know who peoples’ second choices are,” Teske said. “We assumed that when Hancock got 40 percent of the vote and others got 60 percent that that was 60 percent anti-Hancock — but some of them might have been Pen Tate fans and/or Calderón fans.

“And in the second round, their true second choice was Hancock — or he was a higher choice than Giellis.”

Was Hancock a “second choice” for many May voters? Maybe, but that’s less important than whether or not Giellis was the “second choice” for non-Giellis voters in May. Roughly 60% of voters chose someone other than Hancock in the first round of balloting…but 75% selected someone other than Giellis.

In short, Hancock never had a math disadvantage going into the runoff election. With 25,000 more votes than Giellis in May, the math was always in his favor.

Many political observers got carried away when Hancock failed to surpass 50% of the vote to avoid a runoff election, forgetting that Hancock still beat Giellis by nearly 14 points in the first round of voting. A 14 point margin isn’t as significant of a number in a four-candidate race, but it’s huge in a two-person battle. It’s no coincidence that Hancock won the runoff by nearly 13 points.

The 60/40 number is where this entire evaluation goes awry, because it is based on the faulty assumption that Calderon/Tate voters would refuse to support Hancock. “Anti-Hancock” and “Someone Else” are not the same thing. Pointing out that 60% of voters initially selected someone other than Hancock is different than saying 60% of these voters flat-out refused to support Hancock.

Fox 31 wondered if Hancock could “steal” enough voters away from Calderon/Tate supporters in order to win the runoff. He actually didn’t need that many of them. Because Hancock had such a big lead from the jump, and because turnout was lower in the runoff, Hancock only needed about one-third of the Calderon/Tate vote in order to beat Giellis. Roughly 15,000 fewer people voted for Mayor in the runoff election; Giellis still would have come up short if every last one of them had voted for her in June.

We often see the same faulty analysis before a General Election when the topic of Unaffiliated Voters comes up. “Unaffiliated” voters represent a little more than one-third of Colorado’s registered voters, followed by Democrats and Republicans. The lazy math is that a Democrat or Republican needs to hold their base and pick up 50% +1 of the Unaffiliated vote in order to win a General Election. But this assumes that 100% of Unaffiliated voters are up for grabs. They aren’t. Unaffiliateds aren’t a bloc of voters; the word “Unaffiliated” just means someone who chooses not to identify with a party affiliation. “Unaffiliated” is different than “Independent,” but the terms are regularly interchanged.

So, why did Hancock win a third term as Denver Mayor? Two reasons: 1) Hancock had more resources available to him than Giellis, which is also a function of support, and 2) Giellis was an awful candidate.

Here’s what Giellis had to say to Westword in a post-election interview:

“I definitely think the four-to-one spending advantage and all the resources the mayor had to go after me from every direction made a big, big difference,” she acknowledged. “The negative ads, I think, put a lot of questions in people’s heads and made it harder to bring some of Pen and Lisa’s supporters over.”

This is true. It is also true that Giellis would have had more resources if she had been a better candidate with a better campaign.

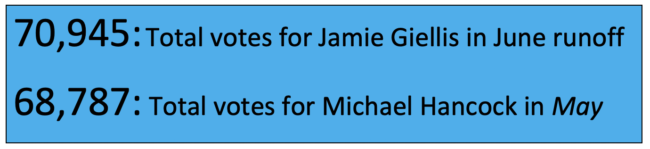

It is doubly-true that Giellis made it really easy to paint her in a negative light. Giellis’s attack ads were disjointed and unfocused. All Hancock supporters had to do was point to Giellis’ own words. The reality is that Giellis lost the runoff as much as Hancock succeeded; Giellis barely managed to get more total votes in the runoff than Hancock pulled down in the first round. As one voter told Denverite two weeks ago: “I’d love to see a female mayor in Denver. I don’t want it to be someone like Jamie.”

In the end, Denver voters demonstrated both an anti-Hancock sentiment and an anti-Giellis reaction. Only one of those candidates could make up the difference.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter to stay in the loop with regular updates!

Comments