January 04, 2018 02:14 PM UTC

January 04, 2018 02:14 PM UTC

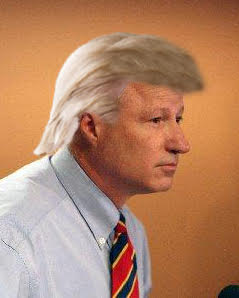

Having climbed the ladder of elected office from the state legislature in the early 1990s, through two constitutional state offices as Treasurer and Secretary of State, and finally as a representative in Congress for going on ten years, Rep. Mike Coffman’s story is one of political survival that few others in politics anywhere in America can match. And it’s not just longevity in elected office: in 2011, the decennial process of redistricting redrew Coffman’s district, transforming Coffman’s constituency from the overwhelmingly Republican south Denver suburbs and exurbs to an economically and racially diverse battleground district centered on the city of Aurora.

Mike Coffman nearly lost his seat in 2012 to an unknown and underfunded Democratic opponent, but recovered in 2014 and 2016 with surprisingly easy victories over much better opponents. In 2016, Coffman won overwhelmingly in a district that Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton carried by an equally strong margin. Coffman did this largely by about-facing on numerous critical issues, at least in terms of his rhetoric–dramatically softening his former Tom Tancredo-style tone on immigration, and audaciously using Planned Parenthood’s logo in campaign ads despite his longstanding opposition to legal abortion.

Donald Trump’s campaign represented a new opportunity for Coffman to triangulate off an unpopular nationwide Republican brand, and Coffman dived into the role with gusto becoming one of the first Republican 2016 candidates to dis Trump in a campaign ad. The margin by which both Clinton and Coffman carried CD-6 is testament to the effectiveness of Coffman’s triangulation off Trump. By a decisive margin, ticket-splitting voters in CD-6 elected Hillary Clinton President and Mike Coffman “to keep an eye on her.”

But as we all know, that’s not what happened.

In October of 2016, when Coffman joined with other swing-state Republicans to call for Trump to withdraw from the presidential race, he did so with no expectation that Trump might actually prevail. When Trump won anyway, Coffman was forced to sheepishly eat his words, declaring that he was “excited” to work with the President. This occurred at the same time as popular resistance to the incoming Trump administration was building toward the Women’s March last January, and then exploded in the subsequent battle over the repeal of the Affordable Care Act that consumed most of 2017 and eventually ground to a halt as the public rejected every version of the plan.

Coffman voted against the Obamacare repeal bill, but only after validating lots of provisions contained within it and doing little to ingratiate himself with the large numbers of upset constituents by then dogging his every appearance. And in the end it didn’t matter: whatever goodwill Coffman might have gained from that vote was quickly squandered by his enthusiastic embrace of the much-reviled Republican tax bill. The GOP tax plan was even less popular than the repeal of the Affordable Care Act, and included provisions that would seriously damage the ACA, but in the end Coffman had little choice but to appease his Republican base and donors.

After all, he’s still a Republican. That simple fact stood out in sharper relief than ever in 2017, overshadowing all of Coffman’s feints and triangulations. With a Republican in the White House and his party in full control of Congress, Coffman has been less successful in the past year putting daylight between himself and the GOP brand than at any point since doing so became vital to his political survival.

Does that mean Coffman’s number is finally up after so much Democratic blood, sweat and tears expended trying to defeat him? After Coffman has held off challengers who on paper should have taken him out, we’re all done declaring his political career to be over. Coffman has demonstrated an ability to weather very intense political storms–and even if the reinvention underlying that continued survival is not authentic, it has worked up to now.

But in 2018, the (R) after Coffman’s name could well be more toxic than at any point in his long career. As Democratic hopes grow for a landslide victory this coming November, with the “generic ballot” showing greater Democratic strength than even Republicans had during the 1994 “Republican Revolution,” Colorado’s swing CD-6 factors heavily in their math. Just like it has for the previous two elections, sure. But this is without a doubt the biggest opportunity for Democrats to flip the U.S. House since they last did so in 2006 under then-historically unpopular President George W. Bush.

Survival against perennially long odds makes for a great story.

But it can’t go on forever. At some point, the odds catch up with you.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter to stay in the loop with regular updates!

Comments